Book review of the biography ‘Bitterzoete overvloed’ written by Hans Werkman

By Martin Maassen, Gay News, 20 November 2011

It doesn’t happen very often that the same biographer writes three biographies about a writer or poet. But now it has happened to the poet Willem de Mérode (1887-1939). His biographer, Hans Werkman, saw enough reasons to rewrite his previous biography from 1983 thoroughly. Werkman discovered new facts and understandings, which justified a third, still more complete biography. And rightly so.

A Boy Case

Willem de Mérode (a pseudonym of Willem Eduard Keuning) wrote during his short life 2,326 poems known to the outside world. “I can’t look at anything or think about anything or I have lines of verse in my head.” Until 1924 the writing was restricted to the moments De Mérode didn’t have to teach classes.

He was a schoolteacher at the Dutch Reformed school of Uithuizermeeden in the province Groningen, but was fired summarily in 1924 because of a “boy case” with Jaap K. From 1911, and until 1971, under section 248bis of the Penal Code homosexual contact between an adult and someone between the ages of sixteen and twenty-one was liable to punishment. For straight sexual relations the age was sixteen.

Looking back De Mérode thought it “terribly, terribly stupid” that he had given in to Jaap’s wishes: “I don’t care about it at all. As long as I may pamper a boy a little. But Jopie did care about it, and because he had been so nice to try to comfort me when Okke left, I said, well then, good, I’ll do it.” It is noticeable, by the way, that Jaap remained a loyal friend during De Mérode’s life…

Okke, who was named Ekko Ubbens in real life, was Mérode’s great passion: “He had golden light brown hair, and astonished blue eyes in an oval, always pleasant face.” According to Werkman, Okke remained “the fair-haired prince of his poetry.” De Mérode’s relations with Okke were severed after the 1924 conviction. The boy’s parents even destroyed all the letters De Mérode had written to the object of his affection.

The Homosexual World

Even before the blow of 1924 De Mérode had gotten in touch with men pf the same persuasion through Master of Laws, esquire J.A. Schorer. In 1911 Schorer had established the Dutch Scientific Humanitarian Committee, after the German example of Magnus Hirschfeld. By these means De Mérode met the teacher Jo Pater, with whom he traveled in Germany, and the well-known man of letters, P.J. Meertens. At an early age he also became acquainted with the life and works of the homosexual German poet August Graf von Platen (1796-1835).

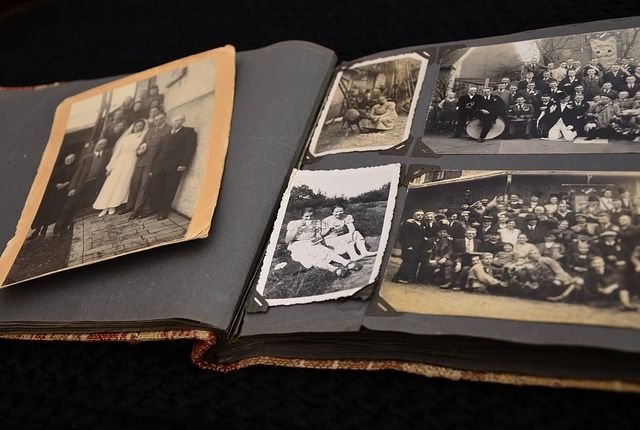

Campers – De Mérode in the middle with cap & portret of the 15 year Okke (Ekko Ubbens)

Werkman writes about him:

“Von Platen fostered the ideal of an enduring spiritual relationship with a preferably fair-haired and artistic young man. Physical sexuality, which he called ‘lust’ or ‘sensuality,’ he wished to avoid; in affectionate self-discipline the relationship had to be ‘a community of celibacy.’ This was just right for Willem Keuning.”

After his prison time De Mérode leaves the northern provinces of The Netherlands. For a short while he is provided accommodation by Annie Mankes-Zernike in Rotterdam, the first Dutch woman minister.

De Mérode (tweede van rechts) met links naast hem de Chistelijke schrijfster Wilma Vermaat – juni 1925

Through Annie Mankes De Mérode ended up on a farm in Eerbeek, where he would reside until his death. He’d become non-denominational at that time.

The consistory of Uithuizermeeden’s Dutch Reformed Church required that he would admit his guild on account of a violation of the Seventh Command (“Thou shalt not commit adultery”). De Mérode refused to comply. In Eerbeek he wrote twenty-five of his thirty-five volumes of poetry. Most of these are deeply religious with a continuous longing for “the fantasized son.”

De Mérode 2nd on the right – June 1925

The Circle Closes

It is one of Werkman’s merits that he has been able to describe De Mérode’s metamorphosis “from neo-romantic to angular expressionist” really well. Without obscuring the struggles and hard facts. In this way he has created an honest biography about a poet who said of himself that he couldn’t sustain the eternal struggles. Therefore it shall be forgiven that Werkman extremely often tries to tell in his very Calvinist way that De Mérode didn’t do “it” with the boys. No “practice,” only sublimation. “Not in the direction of active sexuality,” only a shopping list of friendships with boys.

In 1936 De Mérode was accidentally rehabilitated (his police record wasn’t known) when he received a royal decoration. His personal rehabilitation he had already found earlier, at the moment Okke’s parents visited him at Eerbeek.

But De Mérode’s most important public rehabilitation was undoubtedly the posthumous unveiling in 1997 of a monument in his honor in Uithuizermeeden. An unveiling performed by Okke (Ekko Ubbens). The same Okke who during De Mérode’s life couldn’t and wouldn’t reconcile. And thus the circle was closed at last.

Portret of De Mérode to celebrate his 25 anniversary as a poet – March 1936

Further Reading

- Willem de Mérode, “The Page.” In: “The Eternal Flame: A World Anthology of Homosexual Verse (c. 2000 B.C. – c. 2000 A.D.), Volume Two.” English Verse Translations by Anthony Reid. [North Pomfret], Asphodel Editions, 2002, p. 287

- Robert Aldrich, “The Seduction of the Mediterranean: Writing, Art and Homosexual Fantasy.” London / New York, Routledge, 1993, p. 118-119

- Hans Hafkamp, “The Life of a Christian Boy-Lover: The Poet Willem de Mérode.” In: Wayne R. Dynes and Stephen Donaldson (Eds.), “Homosexual Themes in Literary Studies” (Studies in Homosexuality, Vol. VIII). New York [etc.], Garland, 1992, p. 152-166

0 reacties